In my experience as a professional screenwriter (on projects like Band of Brothers) and in the years that I’ve been teaching and coaching writers, one thing that’s become clear is that projects live or die mostly based on their central idea. Yes, they need to also be really well-executed, but it’s the decisions writers make before they even start beat sheeting or outlining, let alone scripting that are the most important ones. We writers tend to decide what our story will be about and then leap into it too quickly, without vetting the basic idea the way we would a finished script. And yet a project’s success or failure depends more on those initial foundational choices than anything else.

My book focuses on that idea selection process. It identifies the seven elements of a viable story idea — elements which transcend genre or medium, and which don’t tend to be fully understood by most writers. I would say more than 90% of the most important notes I have on any script — my core reaction to whether it “worked” or not — have to do with the underlying story concept. I could’ve given those same notes on the logline, or a one-page synopsis. And that’s what I do with my coaching clients, who smartly come to me before they’ve done much more than that.

Every story (and its logline) can be reduced to a problem that really needs to be solved. Or it could be a goal that really needs reached. They are two sides of the same coin. It’s a problem that one hasn’t reached their goal, and their goal could just be to solve a problem. So we could call it the “problem/goal.” When we’re telling someone what our story is about, that’s what we’re really talking about — it’s central problem, why it’s important, why it’s hard to resolve, what’s in the way, and most of all, why the audience should care.

In my book, I’ve broken down the word “problem” as an acronym into the following seven qualities, which I think are present in stories that really work:

PUNISHING. The problem defies resolution, despite its main character actively pushing and struggling through virtually every scene, which mostly just leads to complications which build the problem.

RELATABLE. The audience has strong reasons to emotionally identify with the main character (and possibly others), such that they really invest in a particular outcome, almost as if it were happening to them.

ORIGINAL. The idea breaks new ground in some way, and has a fresh and distinctive voice. But it’s also a fresh twist on a proven and familiar type of story or genre. It doesn’t completely reinvent the wheel.

BELIEVABLE. What happens and what everyone does and says makes sense and adds up, striking the audience as very “real” — even if there are some fantastical buy-ins they have to make at the story’s beginning.

LIFE-ALTERING. The “stakes” are enormous, in terms of what is to be gained or lost. Very important things hang in the balance for these people we care about. It really matters, for all to be right with the world.

ENTERTAINING. The process of watching the main character try to solve their problem is truly fun to watch, in one of a handful of proven genre-specific ways that audiences pay to experience, emotionally.

MEANINGFUL. The story is “about something” that feels like it matters to the audience’s lives or sense of the world at large, somehow. It explores something fundamental an important to the human condition.

These qualities might seem to be self-evident, as the stories we love tend to accomplish them with seeming ease. But they are all harder to achieve than it might seem, and they take conscious effort on the writer’s part. Each one contributes to grabbing an audience and keep them engaged. Which I think is what we’re all trying to do, whenever we write something.

There are several dimensions to each of these, which the book explores at length. And there are differences between how film and television displays some of these qualities, which is why each chapter exploring one of these ends with a section on how they apply to television.

For instance, in television, a typical episode tends to have more than one story, each with its own main character. Every story needs to engage the audience by having these seven elements, but the problems tend to be part of larger problems that will exist for the entire series. That doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be some resolution at the end of an episode, though. If there isn’t, the audience doesn’t feel like they’ve watched a story — just a collection of scenes that are part of some much larger story.

When a writer sells a project — be it for TV, film, stage or commercial fiction — it tends to be mainly because the buyer believes the idea exhibits these qualities effectively. When they pass on a project (or ignore writers who have queried or sent them material), it tends to be because they don’t. Professional-level execution on the page is a given that is expected and needed as well. But assuming that, “the idea” is what really matters.

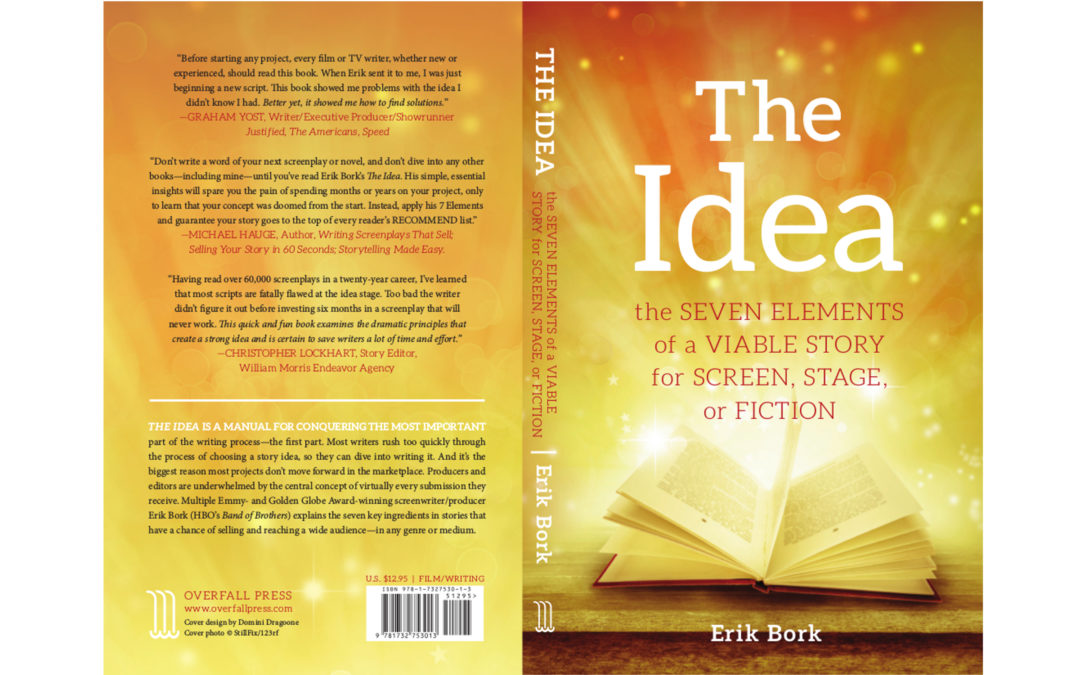

To download a free sample chapter and read some of the nice things people like Graham Yost (Justified, The Americans, Speed) have had to say about the book, head over here. Or check it out on Amazon, where it’s available in paperback, Kindle e-book, and audiobook, read by yours truly. I’m happy to say the reviews so far have been pretty amazing!

Yeah, yeah, we know this after analyzing really great stories. How those stories came about, however, is not so clear. That’s the crux. Writing a script is often an exploration of an idea, an ambiguous feeling, a subtle melody one simply feels compelled to start humming. Only by starting to write it down does it become clear to the writer what exactly he is exploring — and that clarity may not come until after many, many pages. Often the writer can go back and shape his or her story into a great story only after he’s hit by that clarity. Not everyone is an outliner. Patricia White’s comment above (or below?) makes me feel for her. She should start writing from her heart, and never mind what we say here. Writing is a solitary, contemplative experience. Beginners should not be intimidated, since all writers are beginners. I would tell Patricia, writing is a hunt, and it should be fun for you. Make it fun or you may give up.

Other books get caught up in over complicating the process, coming up with novel names for structure points. But this book is so powerful but keeps it simple. One of the very best screenwriting books. A must have

I don’t DARE write a word right now.

I thought I had a story, but reading this I realize I don’t because what it boils down to is that the protagonist doesn’t really want something, so I cannot move forward.

I thought about stories where the ‘really wants’ rolls off my tongue. Buddy really wants his dad to love and accept him (Elf), Michael Corleone really wants to “be here for you, Pop,” (Godfather), Andy Dufrense really wants to survive while he’s in prison (Shawshank), Rose really wants to be with Jack (Titanic), Erin Brockovich really wants to stick it the bad guys at PG&E (Erin Brockovich), and Shrek really wants to overcome his own wall, peel off his layers, and fight for love (Shrek).

So, until I know what mine really wants, I’ll keep on studying and thinking.

I have to keep telling myself that I will write a good story.

Keep calm and write something worthy on.

Thank you, Erik, for pointing out the obvious that I didn’t see.

I look forward to reading The Idea.

Erik,

Your “Problem” acronym nails the key principles that great stories must-have. I’ve found myself telling others about it, so you’ve definitely made it easy to remember. Love it! Thanks!

This is exactly what I am struggling with right now (and always). I’m notorious for false starts when drafting. Read some of your posts on different Save the Cat genres and I just purchased your book. Thank you so much!

Glad to hear it Lara — thanks for buying it and I hope it helps you!

Perhaps the best and most concise advice ever given.

Thank you so much David!