What is a B Story?

It’s a secondary story that has its own beginning, middle and end, and is focused on its own problem, separate from but intertwined with the A Story.

And it has its own main character, who may or may not be the same as the A Story’s.

Movies typically have one. For some very good reasons. But writers often have some confusion about how a B Story should work, and what it should be. I see this coming up a lot with both my consulting clients and students in my online course.

Just like the main A Story, the B Story’s main character should have a problem involving something external, which has its own significant life stakes. That means the problem isn’t only an internal issue, involving their need to grow and change in some way. Although it usually does touch on that in a more pointed way than the A Story.

The classic use of B Story in a movie is a romantic relationship that is secondary to a non-romantic A Story. The potential romantic partner often pressures the main character, intentionally or not, to deal with their “stuff,” and consider changing. But as with most such internal growth, the character doesn’t engage in it willingly, with “growth” as the goal. No, characters (like real people) tend to avoid change, until really significant external problems force them into it. Typically the pressures of both the A and B Story problems combine to do that. But even then, the hero usually doesn’t really change until some key moment in the final act where they (usually) snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

But first, both A and B Story usually reach a rock bottom “All is Lost” moment. So if the B Story is about a relationship, it’s usually broken and over at that point, as are the main character’s hopes for their A Story goal. They will have one last chance to try to solve both in the final act.

If the B Story is a romantic relationship, something has to be in the way of it. It has to be focused on a conflict, and not going well. If two people fall for each other and get together and have a lot of sex, etc., without some looming threat to the relationship, that’s not a story. That’s a positive development for the main character. And we audiences get bored by positive developments. We thrive on problems and conflicts.

Save the Cat’s “Beat Sheet” positions “B Story” after the Break into Act Two and before the “Fun and Games section.” Meaning the B Story begins there. Or you could say its “catalyst” or “Inciting incident” happens there — the thing that rocks the main character’s world and begins the story. It will then build and complicate, like all good stories do, as its main character attempts to resolve it, or deals with its difficulties.

So classically the A and B Story in a movie have the same main character. But that’s not the only way it’s done.

In movies with romantic A Stories, each of the two people in the potential couple typically get a story. They might feel like “A” and “A minus,” almost equal in weight, instead of one main character getting both A and B Story. Each has their own problem with a beginning, middle and end. It might be about the relationship, or about something else going on in their lives.

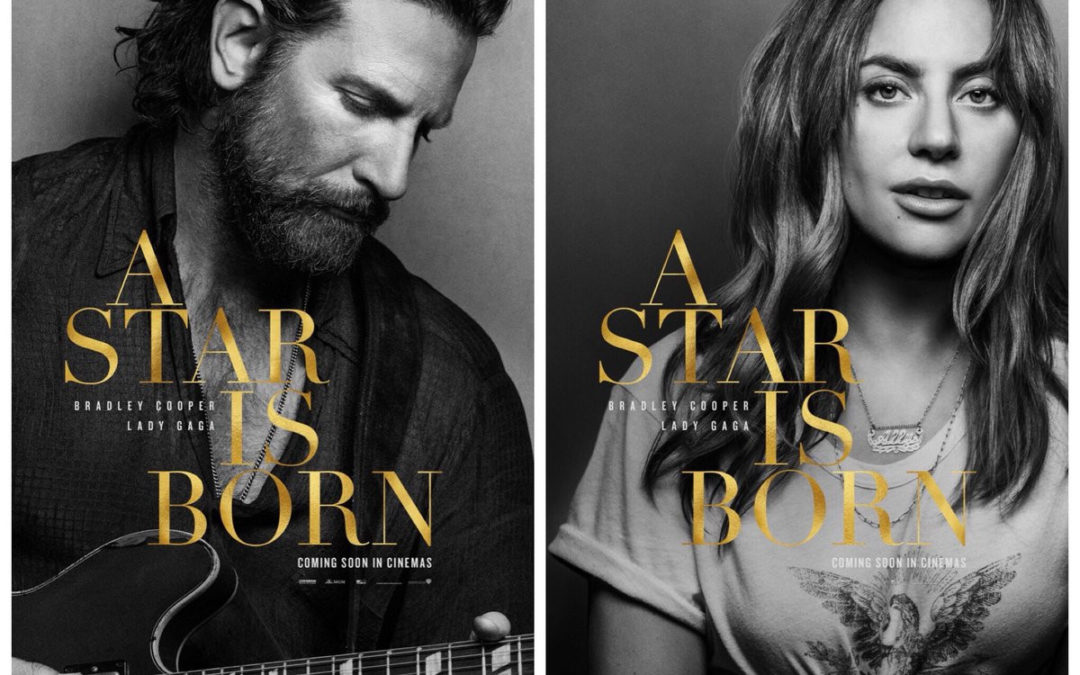

If you look at the latest remake of A Star is Born, for example, each of the two leads has a story we pursue from their perspective. Bradley Cooper’s character has demons and an addiction that isn’t resolved, which causes problems and conflicts in his life and relationships. (Note that if it didn’t cause such problems he had to deal with, and was only internal, it wouldn’t work as well.) Meeting Lady Gaga gives him some fresh hope but also new challenges around all of that.

Lady Gaga’s character meets this man and has a whirlwind rise to fame and romance with him, but it’s all tenuous and filled with problems that make it hard to enjoy in a sustained way. (Not unlike Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody.)

So there are two intertwined stories. We get to experience things from both of their subjective perspectives, going back and forth between them, throughout the movie. It’s not that the point-of-view is objective, and we’re looking AT the two of them. Instead, we look THROUGH him at times, and through her at times. It’s a subtle difference, but a crucial one. (I first got this lingo from the Dramatica theory and software for story, which has an intriguing take on how most great movies really have four “throughlines,” one each for the main character and their “influence character,” plus another about their relationship, and a fourth about the overall problem that affects everyone.)

Point-of-view is such a key thing to master in screenwriting: how to make the audience feel things from one character’s perspective, and staying in that perspective whenever we’re in their story — which means staying focused on their emotions, desires, and what they’re actively trying to do to get what they want. I explore this more in the “Relatable” chapter of my new book The Idea.

Some “ensemble” movies (and most TV episodes) have more than two stories going on, so you might have A, B, and C stories, and sometimes many more. (Usually each one has a different main character, but sometimes you’ll see a character get two stories in one TV episode, like Buffy in a typical Buffy the Vampire Slayer getting both an action/vampire story and a teen personal life story.) But the principles are always the same. At any given time, we’re in one of the stories, and focused on its main character’s current focused problem and desire, how they feel about it, and what they are doing to try to resolve it. And it builds and gets worse, leading to a crisis, then a final climactic “battle” of sorts where it gets resolved.

If you don’t have a B Story (and don’t have that “influence character” Dramatica talks about), your script might lack depth. And in a pilot, this is especially a problem, since TV is so much more ensemble based and eats up so much more story than a movie. A singular A Story usually isn’t compelling and rich enough to be the only thing going on, and sustain audience emotional investment throughout.

So a B Story really isn’t optional. But the good news is that it’s often the thing that writers are most interested in, where they get to explore the stuff that really made them want to write the script in the first place. The A Story might and probably should fit within a certain commercial genre (like the medical stories in House, M.D.) but it’s the secondary, more personal B stories that might be what the audience most connects with, what stays with them, and what also excites the writer.

As that show’s creator David Shore once said, “There is a procedural spine, but I wouldn’t watch it for the medical stories. Frankly, it would bore me.”

Well written Erik, thanks.

Hi Erik,

Really struggling with my B story and your article is helping me see it better. Thanks!

Question, have you ever seen two B stories before? I don’t mean a B and a C story. I mean one B story that begins and ends before the mid-point and then a second one that begins and ends by the end of Act II?

Thanks.

Mark H.

It’s not something I can think of ever seeing, although that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Normally all stories in a movie run pretty much to the end. Sometimes the goal can seem to shift somewhat in the middle, but I think if you look at the overall sense of problem and an outcome the audience might want, that tends to stay pretty consistent.

I LOVE you book Erik. It’s practical, a good read, and vital information.

Thank you so much Michael!!

I have been loving your book. It is a perfect tool to have in my toolbox.

I reference it for every idea that I have not been able to figure out.

It has an answer for every story.

Thank you for putting your earned wisdom in my hands.

The Idea is a perfect fit!!

That’s so nice to hear, thanks Mikki!

Thanks for another great article.

One of my favorite applications of intertwined A, B C-stories is Burn Notice (Matt Nix, 2007–2013), if you saw/ remember that one.

Glad you liked it Kevin! I never really watched Burn Notice but I did know some writers who worked on it…

It is interesting that you chose A Star Is Born to illustrate the notion of the B-story because it is far from classical in the sense that the B-story – the Cooper/Gaga relationship – is the bigger of the two. It is why audiences are flocking to A Star is Born, not the Cooper character’s demons, which really constitutes the B-story. The heart of the story is the shifting points of view on the Cooper-Gaga relationship, which is not especially well done. Indeed, we never quite get to understand what Cooper’s problem is with Gaga’s rise (it’s all a bit fuzzy). Overall, movies with two equally weighted central characters tend to screw with the idea of the hero’s journey or single point of view.

Thanks for the comment Mark!

I guess I see it a little differently. I don’t see the relationship as the B Story. I see his story problem as one of two stories and her story problem as the other. You could call them A and B or A and A-, I suppose. I’m not sure which is more prominent. But they each have a challenge that includes the relationship but is not just that — it is more of a gestalt of where their lives are at the moment. I suppose in Dramatica terms you’ve got those four throughlines going on, one of which is “their relationship,” but if we talk in terms of just “A Story” and “B Story,” that’s how I’d see it.

In any case, I don’t disagree with your critiques. I just used it because it was a current example of something we see over and over again in romantic movies where it can be tricky to balance the two characters’ situations and yes, it commonly does take us out of the “hero’s journey” or single POV model.