Subtext is often talked about as the key to good dialogue.

But what is it, exactly, and how do we use it?

Subtext is what characters are really thinking, behind what they’re actually saying.

In the best dialogue, the two things tend to be different. The audience (and perhaps the characters) can sense what the person who’s speaking really means, wants, feels, and thinks, but they’re not coming out and saying it.

An example from the 2018 movie The Favorite:

Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are out shooting. Rachel asks Emma if her secrets are safe with her. Emma says “Even your biggest secret.” SPOILER ALERT: That secret is that Rachel and the queen are lesbian lovers. Emma doesn’t come out and say that part. But she reveals she knows it with these four words. And Rachel gets what she’s talking about.

Then Rachel points her gun at her and shoots! Emma falls to the ground, stunned, checks herself for wounds, and Rachel says, “If you forget to load the pellet, the gun fires, makes the sound, but releases no shot. It is a great jape, do you agree?”

What’s the subtext here? What is Rachel really thinking? What is the meaning behind her words?

To Emma (and to the audience), it’s crystal clear: “You screw with me, and I will end you.”

Now how interesting would this scene be if Emma had said, “I know you have sex with the Queen,” and after firing the gun, Rachel said, “If you tell anyone, I’ll make you regret it”?

A lot less interesting, intriguing, and compelling, right?

That’s subtext.

As in real life, good characters don’t tend to just blurt out everything they’re thinking and feeling. Unless they’re small children, perhaps, or if they’re caught off guard, or under the influence of something, when they might start to have “loose lips.”

Most of the time, though, we are a bit more guarded and calculating (even if we don’t realize it). When we speak, we’re saying what we think is the right thing to say to advance our agendas in some way. We know that hiding our full true feelings and intentions is often necessary and helpful. This doesn’t have to come off as dark and manipulative. It’s just human and normal.

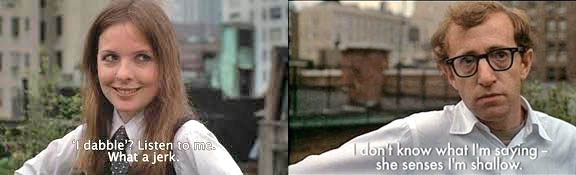

Consider the classic scene in Annie Hall: Woody Allen is dropping Diane Keaton off at her apartment. They just met. There’s an attraction. So he begins making conversation about the photography on the wall, but what each of them is really thinking is subtitled for the audience. And it’s thoughts like “I wonder what she looks like naked,” and “I hope he doesn’t turn out to be schmuck like the others.”

It’s funny, because we can all relate. We’d never say those things that are really driving us in that moment. It would be a bad move on our part. It wouldn’t serve our interests.

Here, in contrast to The Favourite (where the subtext was crystal clear to both Emma and Rachel), the two characters might be only vaguely aware of what the other person is really thinking. They’re more concerned with what they themselves are thinking (and most importantly, feeling and wanting).

Robert McKee analyzes a similar (but more dramatic) scene from Casablanca in his book Story — providing the dialogue between Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, and what each is really thinking, wanting and intending, with every line of dialogue. It’s the section I remember and recommend to people most, in that classic book.

The audience usually has a pretty good idea of what the subtext is — and what the characters are going through. If they didn’t, the scene would be a lot less interesting. It might even be confusing. If we sensed there was subtext but had no idea what it was, we would just feel kind of left out. Or if we didn’t get that there was subtext, and just took everything at face value, the dialogue would feel flat, obvious, and less involving.

So how do you make sure the audience gets the subtext? In the examples above, it’s fairly obvious, even if you don’t know the characters that well. But often, “getting the subtext” is dependent on the audience (or reader) understanding what a character is going through and wanting in the scene, and what they’re trying to achieve. And that’s what makes it interesting — the difference between what they say, and what we know is really going on.

A very common issue I see in scripts is the writer not making sure the reader/audience knows the main character well enough, and is emotionally connected with them, and experiencing the story subjectively through their point-of-view. Then it’s hard for the audience to engage fully and care enough, because they haven’t been given that deep immersion into what’s going on with the main character (including in the opening pages), and aren’t being clearly shown what the character wants, thinks, feels and is trying to do, at all times. It’s best that the main character isn’t mysterious to the audience, usually. Instead we want them to feel they sort of become the character, even wanting what they want, and caring strongly as they go about trying to get it.

If the audience is really bonded to a character in this way, where most scenes are about them trying to get what they want and encountering conflict, we will understand what they’re really thinking when they say the things they say. We will also get why they’re choosing the words they choose. We might understand this for more than one character in a scene (as in the examples above). But we especially want to get it for the character who is driving the scene with their intent, which is usually the main character of the movie (or of the currently active story in a multi-story movie or TV episode).

One last example of subtext, from a scene I was fortunate enough to write, is in the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers, in Episode 8: “The Last Patrol.” Damian Lewis as Maj. Dick Winters is prepping some men for a patrol he’s supposed to send them on that night. Everyone in the scene knows that one of their comrades died on a similar (seemingly pointless) patrol the night before. As he’s talking them through the plan for this coming patrol, tension rising, he ends by say something that is initially surprising, to them and to the audience:

“In the morning, you will report to me that you made it across and into German lines, but were unable to secure any live prisoners. Understand?”

Imagine how less compelling the scene would’ve been if he’d simply said, “Col. Sink wants you to do another patrol tonight, but I don’t, so just give me a report in the morning that you did one, okay?” It wouldn’t even be a real scene. It would just be a line of dialogue, with little conflict or interest. It’s the build-up to a patrol we (and they) think is happening, and then that “turn” at the end, using subtext, that makes the scene.

Not every line of dialogue in every script has to be brimming with subtext. Sometimes people really do just say what they mean, think, feel and want. But in general, subtext adds depth, believability, intrigue and entertainment value. It enriches the dialogue and gets the reader more emotionally involved. It’s also a way to explore how each individual character has a different “voice” — how they express themselves in their own unique ways. This includes the extent to which they use subtext, and the kinds of things they tend to say, compared to what they really feel.

So to sum it all up, here’s what I recommend:

Work to know what your characters really want and feel, at all times, and put them into scenes where they will face conflict, where they can’t easily get what they want. Then choose dialogue that makes sense for them to use, given their agenda and feelings, but which doesn’t necessarily reveal their whole truth.

Readers and audiences will thank you.

Invaluable piece of information. Thank you!

Thank you, Eric. Great article. Very helpful.

Thanks Eric!..A question:In one scene is it possible to make the idea that the protagonist’s desire is to go forward but the conflict with the other character shows that he does not have enough elements; the conflict indicates that it must stop and look for allies and this is indicated, in the subtext, involuntarily, by the antagonist?

I’m not sure I fully understand your question. Maybe email me at erik@flyingwrestler.com to discuss further…

Good article.

Thanks for all the kind comments, everyone! It’s really gratifying to know that you find value in the article, and I appreciate each of you taking the time to comment!

Wonderful article, with all the links it’s a veritable CliffsNotes review of the high points of The Idea (I’ve read twice), and then some. The commentary delineating miniseries vs. movies, in the context of ensemble characters, was invaluable clarification for me, even after our one-hour phone consultation several months ago. I’m becoming a believer, well done!

So very true. Excellent examples and perfect reminders. Thank you.

I think the subtext of Eric’s article is: subtext with a PUNCH beats everything. Good! K

You are a true master of decorum and subtlety, Mister Script-doctor extraordinaire! Thank you again for another brilliant post!

As always, excellent post. The “how not to write it” examples make the point beautifully. Thank you Erik.

Very good article about subtext in screenplay… I like it

Thanks Eric, this was a good one.