No one warned me that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was going to be 2 hours and 40 minutes long.

Or that it would be paced the way it was.

Certainly the trailer suggested a fun, breezy, upbeat romp.

I knew there would be exaggerated violence of some kind. There had to be. It’s a Quentin Tarantino movie.

But what I found myself mostly feeling… was a little bored. Much of the time.

HOWEVER…

The film has stayed with me. And there were moments that I thought were fantastic.

So on one hand I admire it and am glad it exists. I’m glad I saw it. I’m intrigued by much about it.

But I thought it would be useful to explore why it didn’t garner a more enthusiastic reaction from me overall. By focusing, as always, on script choices.

And there are two main reasons. SOME SPOILERS FOLLOW.

1. The scenes are very long, and often not much is happening, dramatically.

When I see (or write) a script that goes significantly over what is usually thought of as the ideal page count (let’s say 100-110 for a feature), usually it’s not so much a matter of there being big cuts to make. Although writers who send me such scripts often ask me to “look for cuts.” Usually the extra length stems from the overall approach the writer has taken. Which tends to mean “long scenes.”

Now if it’s a very early draft, it’s normal to be “long.” And I usually say that if you focus on the creative issues, overall, the length will come down as a by-product. So it’s not about trying to make it shorter, as the primary goal. It’s about approaching scenes by identifying what is crucial — what the scene is really about — and then getting to it quickly, and then getting out quickly.

Tarantino is not known for this. He’s known for extended scenes. Most of the time, in the movies of his that I know well, that works, because of a combination of appealing dialogue, cool/interesting stuff going on and just great filmmaking. But also, most of the time, there are intense life and death stakes, and a lot of built in tension. Take the opening sequence in Inglourious Basterds. Or virtually anything in Pulp Fiction that isn’t in the 1950’s diner. That tension keeps us on the edge of our seats.

In most of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, we don’t have that. No life and death tension. But still very long scenes. The filmmaking is great, the acting is great, and sometimes the dialogue is intriguing. But whats missing, often, is a major dramatic problem or conflict that I really wanted to see solved.

2. No “main character” actively pursues resolution to an overall problem or goal.

We’re essentially following three people in this movie, and though each has problems or potential problems, there isn’t exactly a “story” in the traditional sense where they spend the whole movie trying to gain resolution to something important to them (and encounter complications which build the story).

Leonardo DiCaprio has a compelling problem in that he thinks his acting career is over. But the movie doesn’t give him a “set-up” section where it’s easy to get on his side and care that much about this. He’s depicted as kind of a self-absorbed actor having a pity party. Which is fun to watch at times. But he’s not really actively pursuing a fix to his situation, that the audience is super on-board with, I don’t think.

He’s given an opportunity to do Italian westerns, and isn’t sure he wants to. Then he goes to do another guest spot on a TV western. He’s not real enthused about this. But circumstances transpire to make him feel like he wants to do a good job as an actor that day. It’s not that he’s going to fix some larger problem in his life with this. But his early stumbles on the set plus a conversation with a child actor (in a very long scene) makes him want to do better. And then he does. (In another very long scene.) After he does, it’s a great moment. He’s moved and satisfied by his good work, which is appealing. Although we’re still kind of laughing at him.

Maybe this good performance of his inspires something that leads to better choices and better career prospects later, but we kind of skim over all that as we jump ahead in time to a fateful summer evening in 1969, where he will face a new and very different challenge (and a pretty severe genre switch). When that is resolved, there’s a powerful moment where we sense that now he could be moving into a better future, as he finally gets a chance to meet his “new Hollywood” neighbors. But along the way, it hasn’t really been a traditional story of him consciously trying to solve a problem or reach a goal.

This can make things feel slow or meandering at times.

And the other two primary characters have even less of what we’d normally see as “story.”

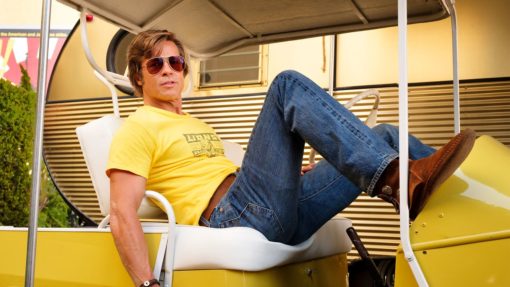

Brad Pitt is a stunt double who can’t get a lot of work these days. But he’s not really doing anything to try to solve it. He’s kind of just living his life. And that’s really what the movie is: 2-3 days in the life of three Hollywood characters in 1969 Los Angeles. Which is depicted in loving, painstaking detail.

This isn’t to say there aren’t entertaining moments with Brad. And even an occasional scene of high tension. Like when he faces off with members of the Manson family at the Spahn ranch. But he doesn’t have a continuous ongoing story problem/goal that he’s actively trying to address.

Margot Robbie has far less to do than either of them. She’s just kind of obliviously living her happy life as an up-and-coming young actress, unaware of any real problems. So her scenes seem like they establish her as a nice person, but that’s pretty much it.

But still the movie got solid reviews and won some major awards. And it has a lot of fans. So what is a writer to take from this?

It might be obvious to say, but I’ll say it:

When you’re Quentin Tarantino, you can kind of write what you want, get financing, and make the movie. And he’s been doing this since Reservoir Dogs. If you’re making a movie independently (or are super established already), that’s a very different scenario from a writer trying to break in, in terms of impressing people with a script. I have my doubts that this script would have won over professional readers, if it was coming from an unknown, and gotten sold or produced, or moved the writer ahead.

That’s not to diminish its value and what’s good about it. It’s just that writers often want to cite projects that have been made as evidence that certain things can work in a script and find success. And as I’ve written about before, I think it’s a bit more complicated than that. It’s kind of comparing apples to oranges — a script for a movie in theatres from an A-lister, vs. a script that a writer uses to break in.

I think there’s a lot of good to be taken from this movie, probably worthy of another post. Which someone else has probably written. My main point is that, as much as one might like the movie (or certain things in it), I would caution against taking too much from this as a model of “what works” — and learn from what is causing some to say that it meanders and is overly long.

I watched this on the airplane coming over to France from NYC, and before I read your comments I agreed with them all lol. Well said, sir.

I agree and appreciate your premise here that this script did not follow the conventions of traditional screenwriting, and should absolutely not be a model or format other screenwriters should tackle. Quentin has a history of defying convention and because he’s directed these stories too he’s been able to present his distinct films in a way that has earned him his status. And because his films are so distinct and unique its actually not a surprise that OUTIH has diverted even further from the “fundamentals”, and to be honest I didn’t even realize that until reading this article, because I am able to immerse myself so completely in the Tarantino-verse. But yes there are some major major script “flaws” if u will, but QT will get away with it because he makes it work and because he knows how to present his brand. but for any other writer to reference QT as an excuse for how THEY divert won’t fly, nor should it.

But i can see how some of these divergences can play on an audiences subsconscious without them fully understanding why the movie felt flat to them, and its probably the reasons you laid out. As far as box office goes, (SPOILERS) I do think the negative pub and buzz from the Bruce Lee scene definitely hurt. While it was a bit scene designed to demonstrate Brad’s elite combat skills in what was essentially a draw, the publicity sort of hi-jacked all talk of the movie after the opening with a narrative of “Brad Pitt beat the crap out of Bruce Lee” which no doubt hurt.

I enjoyed the movie, while I did not love it, but it’s length didn’t bother me as I felt like I was like looking in to people’s normal lives in a not-so-normal business. But, besides the climactic Manson family scene, what I enjoyed was the way we see the secondary guy, Brad Pitt, constantly showing fearlessness, stealing the movie from the protagonist.

And, where I expected to see the Manson family tear things up, I loved the twist that Tarantino put on it. If only. And while you point out that the script would probably not have passed muster were it not Tarantino, I recall reading about how a frustrated writer once submitted a copy of Casablanca under another name … only to get a rejection stating that it was a cheap attempt at doing a Casablanca type script! So, who knows. I don’t think Reservoir Dogs was worth watching, and wouldn’t have been, had Pulp Fiction not followed it.

I greatly enjoyed and appreciated your review of Once Upon a Time. It made me think.

Good Blog, which I largely agree with. “You can flout 3000 years of dramatic structure when you’re Tarantino. But I can’t see the same script from an unknown writer making it past the first reader.” Similarly, I enjoyed the film for its leisurely pace, nostalgia, music, painstaking period detail. There’s a lot to enjoy here, and I would see it again. However, my main problem with Tarantino is his insistence always upon extreme violence as the only means of resolution. Whether it’s a fetish, pure laziness or the lack of imagination (I can’t think of anything else) – I find it baffling that such a talented filmmaker would limit his palette to this one color (red). At over 50 years of age, this seems to me juvenile and repetitious. I’d love to see him tackle a more nuanced project or set of characters where their problems are not solved by slamming someone’s head into a telephone. But then, maybe that like wishing for a love song from the Sex Pistols.

I get your point about the absence of a clear cut hero. Was kind of buddy movie? Cassidy and Sundance? But they had no shared goal. And, as you said, it’s not really about either one of them engaged in furthering their careers. A Tarantino movie is like watching the work of a madman. When you find yourself laughing at extreme violence because it’s such an over-the-top spectacle, you know it can’t be good for you. There’s a certain evil genius at work, but don’t get too close if you’re an aspiring writer.

I too was giddy as a gelding to sit down to what might be Terantino’s last hurrah.

However, I found myself in Eric’s head telling me to correct a few dozen escape hatches that wouldn’t or shouldn’t open.

But alas, Tarantino can do whatever the heck he wants because he’s out of box brilliant!

Erik, thanks for pointing out what is obvious, but few would dare say.

I am a fan of Tarantino, but this is by far my least favourite , with the exception of Death Proof. It is a film, I will not watch again, and I have DVD’s of some of his others.

I think this is a perfect example of the Emperor Has No Clothes scenario in Hollywood. After the screening I heard several people commenting on how much shorter this film could have been. In fact I downloaded a version and did a cut, that I think takes nothing away from the plot, and it ran at 1:37 minutes. I think the whole Sharon Tate footage was useless. Except that it led the audience on that some how DiCaprio and Pitt might become involved in that horrendous event.

To me this was a cheat. A bait and switch.

Hello Erik, thanks for this. I wondered about myself “where is the story?” throughout the way too long movie.

I have to take exception to much of what you have written. While this is not my favorite Tarantino film, there are many things about it which reaffirm my passion for his work. I don’t doubt that an unknown writer submitting this to a reader might well get a pass. On the other hand, I think the primary tension in the film is based on the fact that we know how the real story played out, which builds as we await the expected massacre. Then when we get a fairytale ending and all of our protagonists ultimately win, it reflects back on the title which set up that ending. I thought the payoff was brilliant. As far as Ms. Robbie’s performance, I believe it was beautifully crafted to increase the expected horror of her brutal murder consequently heightening that tension and setting up a sense of dread as the film reached its climax. I absolutely loved many of the scenes that you seem to find overly long, simply because they defy the all too formulaic common cinematic brevity and allow us to experience scenes which actually seem like real life. On one point I do agree. Most aspiring/struggling writers don’t have the talent to write long scenes anywhere near as good as Quentin’s, but they shouldn’t be discouraged from aspiring to excellence.

You made some excellent points, and I agree with you %100, however, I did enjoy the film immensely. Why, because yes there were some long scenes, but I love the way Tarantino takes us on this journey into a “once upon time in Hollywood.” The cars, the clothes, and of course the over the top characters – which I love. My thoughts are that Hollywood – or the film industry – mixes reality and fantasy quite often, and sometimes hard to distinguish between the two. And that’s exactly what Tarantino did with this film, he mixes reality, some facts, and fiction. Me essentially mimics Hollywood and filmmaking.

Yes, I agree wholeheartedly that the protagonist didn’t really have a solid goal, want and need, but I do think that Tarantino’s artistic brilliance is that he never nails down a specific genre. He crosses genre’s continually, but that’s what makes his film so awesome to me.

Erik – a big takeaway for me was how powerful a story engine a future “ominous” event – one the audience knows of but the characters don’t – can be. In a lot of cases, the audience is made aware through some non-linear storytelling device.

Here, it’s expected the audience has a cursory knowledge of the Manson Murders, and it’s hinted at throughout the movie (and in the trailer) that the two main characters are at some point going to intertwine with one of the most talked about murder sprees in American History.

Without that dangling over my head, the storyline wouldn’t have kept my interest nearly as much, as fun as some of the scenes and characters were at times.

Hey Erik,

Thanks so much for this article. I left the theater and kept thinking, “What the heck was the point of this movie?”, “Was there any story or plot in it?” and “How the hell did this even get made?” – And I gave myself an explanation to the last question just like you said, “Well, if you are Tarantino, you can do whatever the heck you want.” – But still, it’s really nice to get some reassurance from someone in the industry, ’cause it’s so often that I feel that some movies/scripts really wouldn’t make the cut if they came from unknown people as you say. Having said all that, I did enjoy the film, but that’s mainly because I always enjoy watching Leonardo DiCaprio and to me, purely watching his performance is a delight. But again, casting choices aren’t yours either if you are not Tarantino, so.. 😀

Completely agree!