Save the Cat recommends giving your main character “Six Things that Need Fixing” in the first act. Then, by the end of the script, you show how these have been fixed.

If you’ve read this blog for a while, you know I like to give my take on the concepts and terminology in this very useful book.

Sometimes I find Blake Snyder’s lingo or the way he describes a term can lead to unintended consequences when writers try to use it.

A big example for me is the “Fun and Games” section, which I always say shouldn’t be fun for the main character.

Another example is “Dude with a Problem,” which arguably undersells the size and type of problem in that genre, which is a life-and-death-stakes action movie.

So many writers new to the ten genres think they’re writing a “Dude” because every story is about someone with a PROBLEM. (Which is the focus of my own book on what makes a viable one.)

Six Things that Need Fixing falls into this category for me because I think it tends to lead writers to focus on the wrongness within the main character more than what needs fixing in their outer life circumstances.

While both are important, the former can alienate an audience if it goes too far, while the latter is essential to what I consider the main function of a first act:

Making an audience care, and want to follow the main character.

The very title of Save the Cat refers to this need. It’s another pithy term that I think can sometimes downplay the importance and difficulty — of getting an audience to care.

While having your main character “save a cat” or its equivalent is useful — especially if it’s a self-sacrificing action and not just a “nice” one — I think writers usually need more than one quick moment like that to hook the audience emotionally, and connect.

This is where Six Things that Need Fixing comes in. Of course the number six is arbitrary, but the point is that you present the main character in terms of problems, early on. The question is what kinds of problems work best or are most important.

Internal problems like the “tics and flaws” the book mentions are one type. Blake talks about Josh Baskin’s need to be “big” in Big. And in a later post, he talks about Michael Dorsey’s various character defects in Tootsie — in addition to his main external problem of not being able to get enough good acting work.

Unfortunately, writers often seize on creating internal defects and flaws, and even go all-in on creating somewhat of a selfish jerk main character in the first act. Their priority is a transformational arc where they’ll become a selfless nice person by the end.

While there is some of that in Tootsie and other great films, I think this “healing the jerk” arc tends to be overused and often counterproductive. As I wrote about regarding flaws and arcs, it can lead to the audience not caring enough to want to follow the story.

Because they need to relate and identify with the main character — even sympathize with and like them, usually — to really want to engage and root for them on some level.

That’s why the Breaking Bad pilot goes out of its way to make Walter White the most lovable and sympathetic main character you ever saw, besieged by external problems. People focus on how he becomes unsympathetic as the series plays on, and is therefore an “antihero.” But look at where he starts. You love him and care about him.

Vince Gilligan achieved this by giving him Six Things that Need Fixing (roughly) that were about a crappy life experience: terminal diagnosis, no life insurance or money, no respect at work, mocked by his students… And he just wants to take care of his family.

Now that’s a series that has a broader canvas to explore the character, and purposefully overindexes on initial sympathy in order to arc him in a negative way later.

But it’s instructive about hooking audiences and making them start to care. If you give the main character enough external difficulty and problems (rather than focus on less sympathetic negative traits), I think you’re on the right track.

It’s harder to achieve and more important than writers tend to realize. One “save the cat moment” is usually not enough. My view of the opening ten pages (Save the Cat’s “Set-up” section) is that their main function is to get the audience understanding the main character and their current world and starting to care about them. “Seducing” them into caring, as Michael Hauge might say.

This takes time. It takes a series of scenes of their status quo life, told from their emotional perspective, where we start to see who they are and what needs fixing. The difficulties in their current world and how they deal with them. A sense of what they wish their life was but it isn’t. (Making sure you “show” this in scenes of conflict, and not just talk about any of it in dialogue.)

This usually means it’s NOT about jumping around to other characters and losing the point-of-view. Or making it all about splashy opening sequences (or framing devices) that delay the in-depth immersion into the main character’s “thesis life” that is so crucial.

In this opening “seduction,” I think the most important things to establish is what needs fixing for the main character to have the life they want. It doesn’t have to be six things. It can just be one big one. Michael Dorsey is a great and worthy actor who can’t get a gig. Likable kid Josh Baskin is unable to have the life that he wants because he isn’t “big.”

While on one hand we want him to get over that, as he will by the end of the movie, I think we’re more sympathetic to his plight than we are thinking he needs to change that view. The same with Tootsie: Michael might have his defects but we’re mainly sucked into his external problem that we want to see fixed.

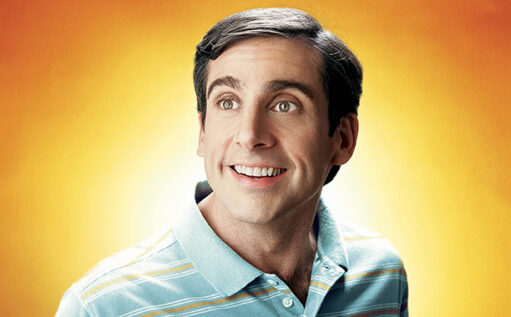

In The 40-Year-Old Virgin the problem is that Andy… wait for it… is a virgin. Meaning that he’s never had sex and that’s a big deal to him. He also doesn’t have much of a social life in general. Then people find out and he’s mocked for it. We sympathize with him greatly.

Yes, there’s an internal aspect to this that will need to heal — he’s given up, he’s all about his action figures, etc. — but he’s not a jerk. He’s a guy in pain who is missing something important. He can’t have the happy life he wants and that we want him to have until this problem is fixed. Not that he needs to have sex necessarily, but this issue clouds his experience and is more than just an inner tic or flaw.

Now I may be partial to movies that really try to get the audience to care strongly about the main character. And this might matter more to “character-driven” movies and can be done with more short-hand in action, thriller or horror.

But I think the best of those also tend to get us investing in the main character in the opening pages with their external life problem(s) — with their wishes that can’t seem to come true — more so than their problematic internal qualities.

Think of Luke Skywalker when we first meet him. Or Neo in The Matrix. Or Harry Potter.

Both the doctor and the kid in The Sixth Sense. Erin Brockovich. Forrest Gump.

Perhaps all of these have some internal flaws or smaller defects that need fixing. And I’m not against that at all. But what they mostly have are unhappy lives with major external problems/goals that aren’t being solved. Before some catalyst rocks their world and sets the story in motion, we see what they wish could be fixed in their life and feel for them.

This is my main recommendation for how to open any script or novel — or TV series, for that matter, which is more likely to have several “main characters” that fit this definition.

Give them external problems in addition to — and more importantly than — the internal ones, so the audience has a strong reason to engage with them from the outset.

I rarely see scripts that really hit the ball out of the park on this front. And as we all know, these opening pages are often the only ones that get read.

If the reader really cares about the main character(s) by the end of them — and it all feels real, original and professionally executed — they will want to read on.

Thanks Erik.

Very helpful. And I agree.

If the main character is too flawed you lose me. It just gets hard to watch. Even if they are trash fires, they need to be likable.

So true… In one screenplay, my protagonist, a young widow with children, had 6 flaws in the set-up. But the contest reader never like the main character, even after her character arc overcame grief.

Thanks, Erik, I appreciate all the blogs you post and I save them in my Erik Bork folder. They really make me think of the various ways I can bring more life, interest, and empathy into my stories when rewriting two of my screenplays. Your blogs and your book make logical sense to me as well as emphasizing the benefits of including a lot of heart within the characters and the story line. My rewrites will have a new life because of your The Idea book and course

Thank you so much Bonnie – that is wonderful to hear! 🙂

Excellent points all! Sounds right to me. Thanks again, Eric!

Nice Erik!

Pulling out the specific of having the main character’s external situation evoke sympathy and caring for them is so appreciated. Giving it emphasis over their internal problems is refreshing to hear.

Hi, Erik – Excellent piece here – thank you – Terry Lynam (Motherkiller, The Warden, The Tree Witch)