When we write action and description in a script, we’re telling the reader what the viewer would see, hear and clearly understand from that.

Nothing else.

This dictates a different approach from other kinds of writing. We don’t get the reader ahead of the audience. We tell the reader what the audience would be witnessing.

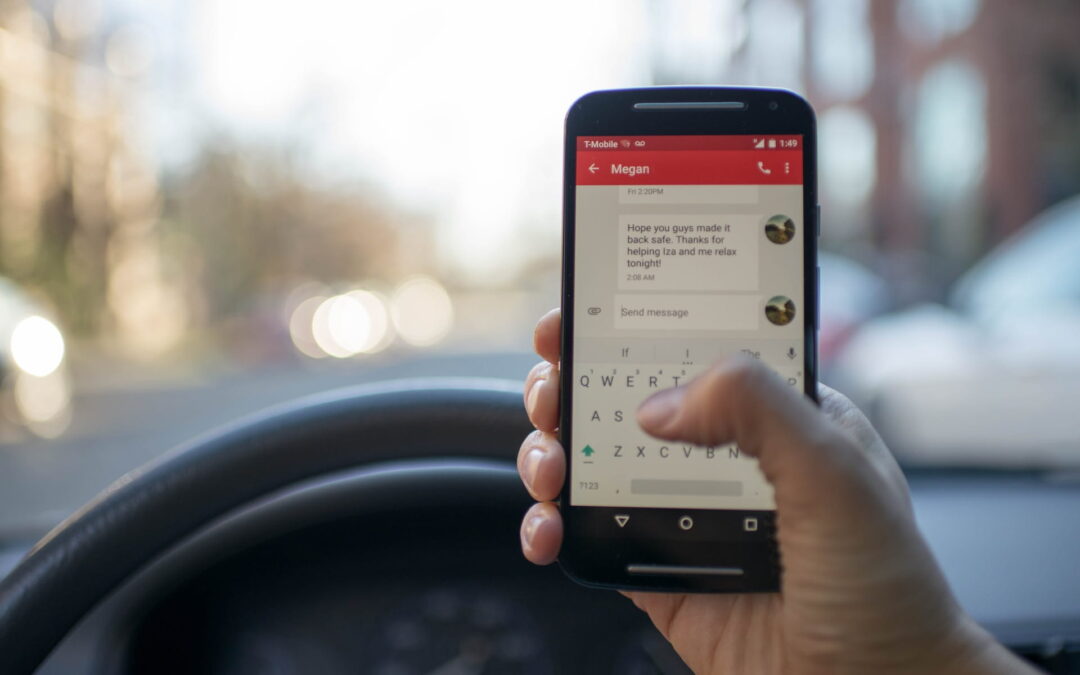

So for instance, when a character is reading or doing something on a cell phone, computer or piece of paper, we want to be conscious of only telling the reader what viewers would pick up on.

Which is usually just the fact that the character is looking at that thing.

Not what they’re seeing or doing on it.

And so we have insert shots. These are close-ups of text or other details that allow the viewer to take in specifics that they wouldn’t be able to do in a wider shot.

Inserts are one rare example where it’s okay and necessary for a writer to do a little “directing” on the page. Usually this is frowned upon, and it’s better to just describe the action an audience would see without indicating camera angles or movements. That’s for the director to decide later.

But with insert shots, you’re telling the reader exactly what is on that phone screen, for instance, so they get what’s happening – and what the character who has it is reading, writing, typing, etc.

The reason this is necessary is that in a typical shot of a character, whether it’s wide, medium or close-up, the audience can’t see the details of what’s on a screen or papers they’re interacting with. All they can see is that they’re looking at a phone, working on a computer, reading something. But we don’t know ANY of the specifics, as a viewer.

The only way we learn the specifics is if the film cuts to an insert shot of said screen and we can read what’s on it.

So for instance, one should never use this kind of description:

“Erik reads a blog article about script formatting.”

Or…

“Erik completes an online banking transaction, sending money to his wife.”

Or even…

“Erik answers a call from his wife.”

Because all the audience would see in these situations would be something like this:

“Erik reads something on his computer.”

“Erik does something on his phone.”

“Erik’s phone rings. He looks at it, accepts the call, and holds it to his ear.”

Followed, perhaps, by dialogue, such as “Hi honey, I just sent you the money.” Which is when they learn who called.

Without the insert shot, the audience doesn’t know much. Neither should the reader.

Only tell the reader what the audience would know.

So how do we do insert shots?

In the first example, you could use an insert of the blog article. Which is just a close-up of the screen that’s tight enough that the audience can read what’s on it.

But even then, you wouldn’t do it like this:

INSERT – COMPUTER SCREEN

A blog article about script formatting.

That’s still too vague. We want specific text that we’d be seeing in the shot. Which unfortunately, as the writer, we have to come up with. And I’m not talking paragraphs of text. This insert shot is going to be on screen for all of about two seconds, so it needs to be something quick and to the point that tells the audience (and reader) what they need to know. Such as:

INSERT – COMPUTER SCREEN

A blog post titled “How to format a screenplay.”

Or you could give specific text from the article such as…

INSERT – COMPUTER SCREEN

An online article scrolls by. We stop on the words “only tell the reader what the audience would see.”

With the second example, the online banking transaction, it could be something like this:

INSERT – PHONE SCREEN

In a Chase banking app, we see “$10,000” about to be sent to “Wife.” Erik’s fingertip presses the “Send” button.

How would they know it’s a Chase banking app? Because presumably it says “Chase” somewhere on the screen. So I’ll let you slide on that.

Finally, with the phone call example, if the audience/reader needed to know the call was from “his wife” before he speaks (and usually you let dialogue and intercutting the other person accomplish that instead), you’d need something like this:

INSERT – PHONE SCREEN

Incoming call from “wife.”

What do you after the insert?

Well, you have to get the reader out of the insert somehow, so it’s usually recommended that you do another all caps line such as:

BACK TO SCENE

And then describe more of what Erik is doing, such as “He closes the laptop and sighs.”

(By the way, these all-caps lines that aren’t scene headings are usually called “SHOTS” in screenwriting software.)

One last note regarding text messages:

Rather than showing close-ups (inserts) of phones with the content of text exchanges, we often see them superimposed on screen instead. That’s perfectly acceptable. It equates to overlaying what would be an insert’s contents on top of the image of the character holding a phone. So you’d describe it as supered and give the reader the exact content of the texts.

I know all of this is a pain and seems super clunky. Why can’t you just tell the reader “Erik sends $10,000 to his wife on his phone banking app?” Surely they know what you mean. And the director will figure out how to make that clear with inserts and/or dialogue.

The main reason is this:

It makes the writer seem like more of an amateur to the reader. And it takes the seasoned reader out of the script because they’re thinking, “The audience has no way of knowing that – why is the writer telling me those specifics?”

Because as I keep saying, description in a script is not just writer talking to reader. It’s a writer describing a finished movie or show to the reader.

And when you read professionally written scripts, that’s one of the first things that tends to jump out — how much the writer is taking the reader on a clear, entertaining ride as they describe what they’d be seeing.

Great info. What about when two people are texting each other on different locations? How does the INTERCUT & INSERT SHOTS would mix? Thanks 🙂

I would handle text conversations the same way as intercut calls with the difference being that most writers don’t format the texting like dialogue. I tend to use action/description margins but put the content of the text messages in quotes and/or italics, while indicating if they would be SUPERED on screen over the picture or would be seen on the phones. (In which case they would be inserts)

Example:

INT. ERIK’S OFFICE – DAY

Erik types something on his phone.

INSERT PHONE SCREEN

It’s a text message to “wife”:

I’ll be late tonight, sorry!

He presses the send button.

INT. ERIK’S WIFE’S BEDROOM – DAY

Erik’s wife notices her phone vibrating. She picks it up.

INSERT PHONE SCREEN

She sees the text from Erik. Types a reply:

I hate you.

INTERCUT TEXTING CONVERSATION

Just as Erik puts the phone in his pocket, he hears it ding, and looks at it.

What would be best practice when writing a scene where 2 people are in different locations having a conversation over a phone and you want the camera going back and forth between the 2?

That would be an INTERCUT CONVERSATION. I suggest something like this:

INT. ERIK’S OFFICE – DAY

Erik has the phone to his ear.

(add some dialogue here, properly formatted, like “Hi honey!”)

INT. ERIK’S WIFE’S OFFICE – DAY

Erik’s wife has her feet up on the desk, talking on speakerphone.

(add some dialogue here, properly formatted, as she responds to him)

INTERCUT CONVERSATION

That last phrase is the key part – in all caps, as a “shot” put INTERCUT CONVERSATION or something similar.

Then you can continue their dialogue and even descriptions of both their actions without going back to a new scene heading to re-establish either of them.

This is done all the time in scripts.

Whenever the scene is over you can just go to the scene heading for the next scene.

Loved this article; so succinct and well-explained. Thanks Erik.

Thank you for the detailed information on this topic. Sometimes it’s hard to know just how to handle these types of scenes, especially with phones and computer screens.

NIce, Erik. Clear, concise “show and tell”. Always a picture of a thing or an action or dialogue. Part of what makes screen writing both challenging and gratifying.

Great info and explanations, Erik! Clear. Simple. Logical. Thank you!