Five years ago this week my book was released.

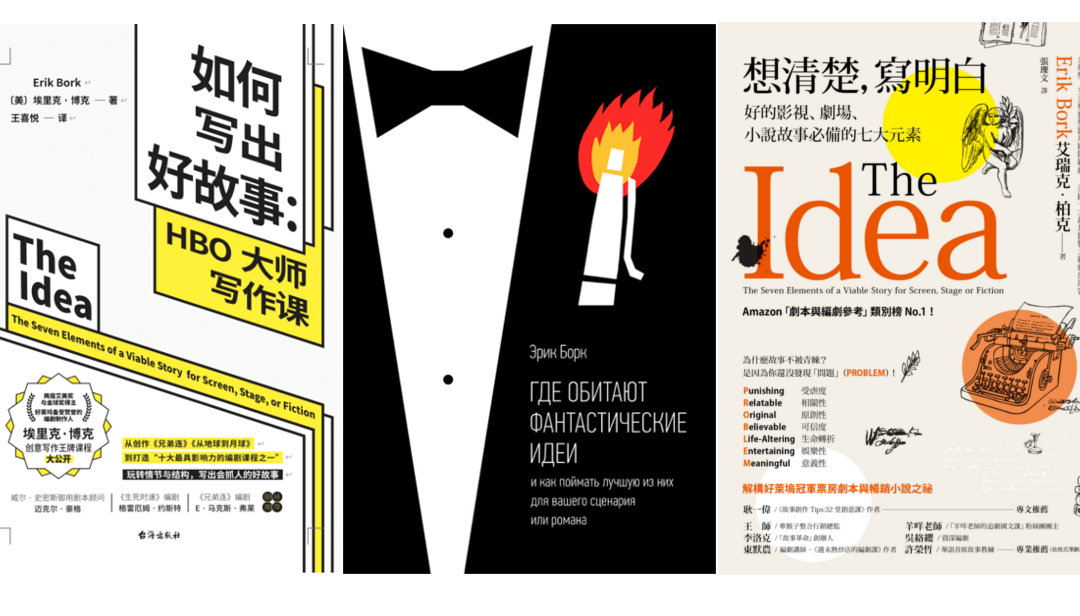

I’m proud to say it’s been translated into Complex and Simplified Chinese and Russian. (See the cover artwork for those above.)

And after about 20,000 sales and 800+ ratings, it holds a 4.7 out of 5 rating on Amazon.

But most of all I like what people say in those reviews or to me in e-mails — that the book does fill a void and has a unique angle on screenwriting and story in general.

That’s very gratifying. Because as I continue to read scripts and work with writers, I observe the same things I wrote about then:

1. It’s a lot harder and rarer than it looks to come up with an idea for a story that really works.

2. Writers tend to jump too quickly into structure, outlining and script.

3. The main notes professionals have on scripts are notes on the basic concept of the story.

This is the argument in the beginning of the book: that it can ultimately save writers time and move them forward faster if they focus much more than they probably do on the idea generation and development process before committing to writing something.

That means understand what a strong idea really needs and working on that with a lot of different potential concepts that they vet and get honest objective feedback on somehow.

The trouble is, most of us writers fall in love with an idea for a story rather quickly.

And maybe people close to us validate us when we tell them why we like it.

And we want to jump in and flesh it out to a format that we can submit to the world.

We’re convinced we “already have a strong idea” and just want notes on the finished script.

Then when objective professionals or gate-keepers of some kind read it, they disagree.

They might not tell the writer that, and might focus on script-level “execution notes.” But usually they have some bigger question or concern about the central story concept. This often doesn’t get talked about, though. For a few reasons:

1. Writers don’t want to get those kind of notes, understandably.

2. Readers don’t want to send a writer back to the drawing board or risk alienating them.

3. There’s not a common language for talking about what a story concept needs, to be viable.

The latter is what I tried to provide, in the book. And it’s what I do in its companion course and with the writers from all over the world that I talk to every week.

I even suggest they send me a one-page pitch or synopsis for their first consultation (which is a lot cheaper than having me read a full script). But usually they send a finished script.

When I read it, I inevitably have considerable notes on the idea that I would’ve had at the beginning of their process. And since they’re the most important ones, they get the focus.

But what often happens is that the writer goes off and tackles all the “smaller notes.” And sometimes resubmits the script to me. And I still have most of the bigger notes, on that draft.

I firmly believe that one of the main reasons why it’s hard to succeed as a writer is that it not only requires a big learning curve and the right psychological disposition, but also this:

A script needs an idea that ticks quite a few boxes for professionals, in order to stand out. It can’t just be well-written on a scene level. It has to be about something that jaded seasoned readers find really intriguing, and emotionally involving. As a story/concept.

In the book I narrowed these elements down to seven that form the acronym PROBLEM.

But if I was to try to boil it all down into one statement that distinguishes the most viable stories (especially for the screen), it would be this:

A single character continuously tries to achieve a really important goal that punishes them, in ways that build and complicate believably, which readers enjoy consuming.

Note: a script might have more than one story going on, with a different main character for each. TV series almost always work this way. As long as they each follow that sentence in bold, we’re good. And when we’re in “that story” we’re in its main character’s point-of-view.

Most scripts and ideas for stories/series tend to have at least one weakness that makes them fall short of this mission statement — that the writer is usually at least somewhat unaware of.

There might be other issues with structure, character, scene writing, theme, etc. but those are secondary. Because they all stem from the foundational choice of story problem and what the main character is doing to try to solve it. (Which is at the heart of a good logline.)

It’s not fun to point out something to a writer that takes them all the way back to their first choices about a story and invites them to rethink those. But it’s what I often find myself doing.

Which is why I love to start at the very beginning, when someone has just a logline, a one-page synopsis, or a brief pitch. And to help them along the way as they build that out.

It probably seems like I’m trying to sell more books, courses or consulting here. And I suppose on one level I am. ![]()

But what I really want for you is to make your process and outcomes more satisfying, efficient and successful by embracing and acting on this approach to writing that I’ve learned, time and again, in my own career and in helping others, is worth following.

I wish this book was around 25 years ago. It will help writers invest their time and effort into what matters most, writing something other people want to read.

Hi Erik,

Congrats on #5! I wish you continued success…

Bob Woods

How many times did you redirect me to focus on the main character, and it was always the right thing to do. Old habits die hard and new vital ones, even as fundamental as staying on the protagonist, might need to be beaten into you by long trial and error.

Erik’s Wonderfully Inspiring Emails are one of the few emails that get read Asap! Thank you 🤗

A share back here is that ALL feedback is Subjective ~ this too, being “Subjective” Feedback! 😄

To seek out “Objective” Feedback, and perhaps even worse, be hoodwinked into believing that any feedback is “Objective”, could lead people up the garden path ~ away from what is so, for them, and what is here to be shared ~ or perhaps even disastrous in some way for themselves, others, or any project they may be working on, in any sphere of Life.

All through following the Conditioned belief system of Others, as to what is what ~ and not!

I have never come across any Professionals/Gatekeepers who are “Objective”

Just belief systems that think they know what is what, and not!

And this can be a dilemma!

Openly Embracing Feedback without falling into perceiving any feedback as being truth of what is so

And for some, perhaps a greater dilemma of how does one get passed Professionals/Gatekeepers who believe they know what is what, and not?

Often Mixed and Mingled with Awe Inspiring Wisdom

Good point Helen – what I meant by “objective” was “not friends and family” or anyone with an ongoing relationship with the writer. It’s ideal if they also do this for a living or something close to it. Though of course every individual’s opinion is subjective. Getting a consensus of multiple opinions and/or listening for what really resonates with you (while willing to be open to anything) is the best practice, I think.

Erik, I always enjoy reading your blogs and of course your book, IDEA. Brilliant and inspirng. And now I have a question about your ‘statement’ that aims to define most viable stories:

A single character continuously tries to achieve a really important goal that punishes them, in ways that build and complicate believably, which readers enjoy consuming.

Are you suggesting that the goal our protagonist is trying to achieve actually ‘punishes’ them? Or is our protagonist ‘punished’ in the pursuit of that goal by other factors, obstacles, characters etc? Why would I (or any character) pursue a goal that punishes me?

And I must admit that I don’t really understand the phrase “in ways that build and complicate believably (or do you mean believability?)”.

I love your work and your writing Eric but I do believe I know what you are trying to say here about viable stories. I think you can say it a lot better.

Thanks so much for the kind words and the question Mark!

Perhaps in trying to be succinct I didn’t explain what I meant enough.

So the “punishing” comes due to whatever people or forces oppose the character’s desire and goal. I see those as built into the story premise. It’s a really hard and unlikely goal to achieve due those forces, whatever they are. And as the main character starts to try to move toward the goal, those forces respond, in a way that punishes them and makes it difficult, and forces them to regroup in some way and try again. Some of this “punishing” is unexpected, some of it is a result of things they tried having unforeseen consequences, which I call “complications.” So the situation “builds” in difficulty, tension, stakes as they mostly fail at what they’re trying to achieve and their actions lead to more problems rather than gradually solving the main problem. To the point where all seems lost at the end of Act Two.

They pursue the goal because it’s extremely important to them and they have no choice but to endure the punishment because reaching the goal is still more important than avoiding the punishment.

I did mean “believably” because I felt that was a key word to throw in. (It’s one of my 7 elements.) Because if somehow these things happen but they’re not believable (which happens more often than you might think in scripts), none of it works.

These other blog posts might be more useful in how they delve into and expand on what I was trying to say in my one sentence:

Punch-counterpunch

Challenges of Act 2

Problem/goal

Who is your antagonist

One big problem

8 types of overall story problem

Make them miserable

A relatable character goes through major life changes while continuously trying to achieve a really important goal that punishes them in ways that build and complicate believably, creating a story which readers enjoy consuming because of its originality, meaningfulness and entertainment value.

😀

As one of Erik’s readers and students, I can affirm this: Having a solid idea foundation is radically important. Before learning this from him, I was rambling in versions of well-written scripts that lacked one central brig PROBLEM*.

Erik’s written lessons are outstanding, but his genius working on live sessions in “The Idea Course” is priceless. He gets to the root problem quickly and has the talent to explain it in easy terms. So, you actually can go and work on it and improve it.

One word: Brilliant!

* PROBLEM is the framework to approach the Idea construction.

Excellent points. And though there are plenty of films produced that fall short of engrossing us, we don’t really want to join that crowd. We’d all like ours to be remembered!

Congratulations on the Chinese and Russian translations! Impressive!

cool, readable, clear) thanks

A neatly distilled summary. Easy to bear in mind. Thanks!

Thank you for another spice of advice Erik!

Thanks so much for this reminder, Eric. It’s very timely and resonates deeply for me. Also congratulations on making your movie, I’m very excited for you.

Spot on!